Medical Journal

Published by

Faculty of Medical Sciences,

University of Sri Jayewardenepura,

Nugegoda,

Sri Lanka.

Original Articles

A Study on the clinically significant Hypoglycaemia among patients with Diabetes Mellitus Type 2 attending the clinics of the Professorial Medical Unit of Colombo South Teaching Hospital Kalubowila

Gunathilake S.H.1, Subasinghe H.S.1, Silva F.H.D.S.1,2*

1Professorial Medical Unit, Colombo South Teaching Hospital, Sri Lanka

2Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Sri Jayewardenepura, Sri Lanka.

*dshehans@sjp.ac.lk

Abstract

Background: Hypoglycaemia remains a significant concern in the management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM), particularly among patients receiving insulin or insulin secretagogues. However, research on its prevalence, risk factors, and management is limited in Sri Lanka. This study aimed to evaluate the prevalence, patterns, and risk factors of hypoglycaemia among T2DM patients attending outpatient clinics at Colombo South Teaching Hospital, Kalubowila.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted with 299 randomly selected T2DM patients aged ≥18 years, and having T2DM for ≥1 year. Data were collected via a validated, semi-structured questionnaire. Hypoglycaemic awareness was assessed using the Clarke questionnaire, and statistical analyses were performed to identify associated factors.

Results: The majority of participants were females (58.2%), aged ≥60 years (62.8%), and of Sinhala ethnicity (86.6%). The prevalence of clinically significant hypoglycaemia was 36%. Key risk factors included insulin therapy (p<0.001), gliptin use (p=0.003), and older age. Skipping meals (75.7%) and excessive exercise (50.5%) were the most common triggers while sweating (73.8%) and hunger (51.4%) were frequent symptoms. Most patients (85%) managed hypoglycaemia with sugary foods or drinks. Only 25.2% made lifestyle modifications, and 81.3% received education on hypoglycaemia management. Despite these efforts, impaired hypoglycaemia awareness was identified in 4.7% of participants, increasing their risk of severe events.

Conclusion: Hypoglycaemia is a common and under-recognized complication among T2DM patients in Sri Lanka. While most patients demonstrated adequate awareness and management strategies, a subset remains at high risk due to impaired recognition and insufficient preventive measures. Interventions targeting education, lifestyle modifications, and individualized therapy are essential to minimize adverse outcomes.

Keywords: Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, Hypoglycaemia, Hypoglycaemic awareness.

Introduction

Maintenance of a healthy lifestyle requires the blood glucose level to be maintained in a narrow range. Hypoglycaemia can be considered when the plasma glucose level is less than 72 mg/dl (4 mmol/l) for diabetic patients. Research on Hypoglycaemia among type 1 diabetic mellitus (T1DM) is more common than Type 2. However, the number of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is ever-increasing in number. This is especially seen in Asian countries.[1,2]

Risk factors for hypoglycaemia are related to therapeutic hyperinsulinemia or failure of defence mechanisms resulting in a drop in plasma glucose concentration. Any treatment that increases blood insulin levels carries a risk of intermittent hypoglycaemia. Patients treated with insulin or insulin secretagogues (e.g. sulphonylureas and meglitinides) are generally at a higher risk. Theoretically, other hypoglycaemic agents such as DDP-4 inhibitors, metformin and SGLT-2 inhibitors do not cause hypoglycaemia because they are not insulin-secreting agents.[3]

The risk of severe hypoglycaemia is higher in T2DM with a longer duration, lesser insulin reserve and other comorbidities including renal impairment, hypothyroidism and defects of counter-regulator hormone secretion. In type 2 diabetic mellitus patients severe hypoglycaemia increase from 7% to 25% in those who have been taking insulin for more than 5 years.[4] A population-based study done in Scotland by Donnelly et al in 2005 showed the incidence of self-reported severe hypoglycaemia in T2DM treated with insulin is lower than in T1DM treated with insulin. Furthermore, the duration of insulin treatment in T2DM is a key predictor of hypoglycaemia in insulin-treated type 2 patients.[5] Miller et al study on type II diabetic patients in 2001 showed a prevalence of 12% of hypoglycaemic symptoms in patients treated with diet alone. This value was 16% for using oral agents singularly and 30% when treated with any insulin (P<.001). Severe hypoglycaemia was encountered in 0.5% of all using insulin. The study also showed an independent association of insulin therapy, lower HbA1c level at followup, younger age and reports of hypoglycaemia at the baseline visit with increased prevalence of hypoglycaemia.[6]

A cross-sectional study done in Saudi Arabia in 2022 by Al-Qassi by a questionnaire via an online platform showed patients with T2DM in the region of Al-Qassim, have insufficient knowledge about hypoglycaemic complicating type 2 diabetic mellitus and they have concluded that the need for interventional programs to raise public awareness.[7] In 2018, a cross-sectional analysis in the USA found that the mortality and morbidity increase in type 2 diabetic mellites patients due to glucose lowering drugs that affect the quality of life, high cost and diminished productivity.[8]

A study done by Dissanayaka et al has found that the most common cause of hypoglycaemia is sudden changing diet, while unaccustomed exercise and non-prescribed native food were the other leading causes.[9] Samya et al in India in 2019 demonstrated a high prevalence of self-reported hypoglycaemia in rural settings. This was in to context of poor resources to monitor glucose levels. The study beckons physicians to probe into hypoglycaemic symptoms in all diabetic patients at each visit. The author also elaborates that it is important to educate patients about the symptoms of hypoglycaemia and the importance of reporting such symptoms, which will help in adjusting the dose and preventing future attacks.[10]

There are many studies done in the world regarding hypoglycaemia in T2DM, but in Sri Lanka, very few studies have been published so far. This study is conducted to find the prevalence and pattern of hypoglycaemia among patients with T2DM, which identifies risk factors, severity and management of Hypoglycaemia.

Methodology

The study was done to determine the prevalence and pattern of hypoglycaemia among patients with T2DM attending the clinics of the Professorial Medical Unit of Colombo South Teaching Hospital, Kalubowila. Two hundred ninety-nine (299) adults with T2DM attending outpatient medical clinics were recruited using the random sampling method. Patients aged 18 years and over and having T2DM for more than 1 year duration were recruited. Those with T1DM and having psychiatric and cognitive diseases as well as acute severe illnesses were excluded. A data collection sheet cum interviewer-administered, semi-structured pre-validated questionnaire with both closed-ended and open-ended questions was used to collect the data on the current topic and those influencing or confounding. The hypoglycaemic awareness was assessed using the Clarke questionnaire which comprised 8 questions where each response corresponds to “aware” (value 0) or “unaware” (value 1) and the scores were then summed. Scores of 0-2 are categorized as “aware”, 4-7 as “unaware”, and 3 as “indeterminant”.

Results

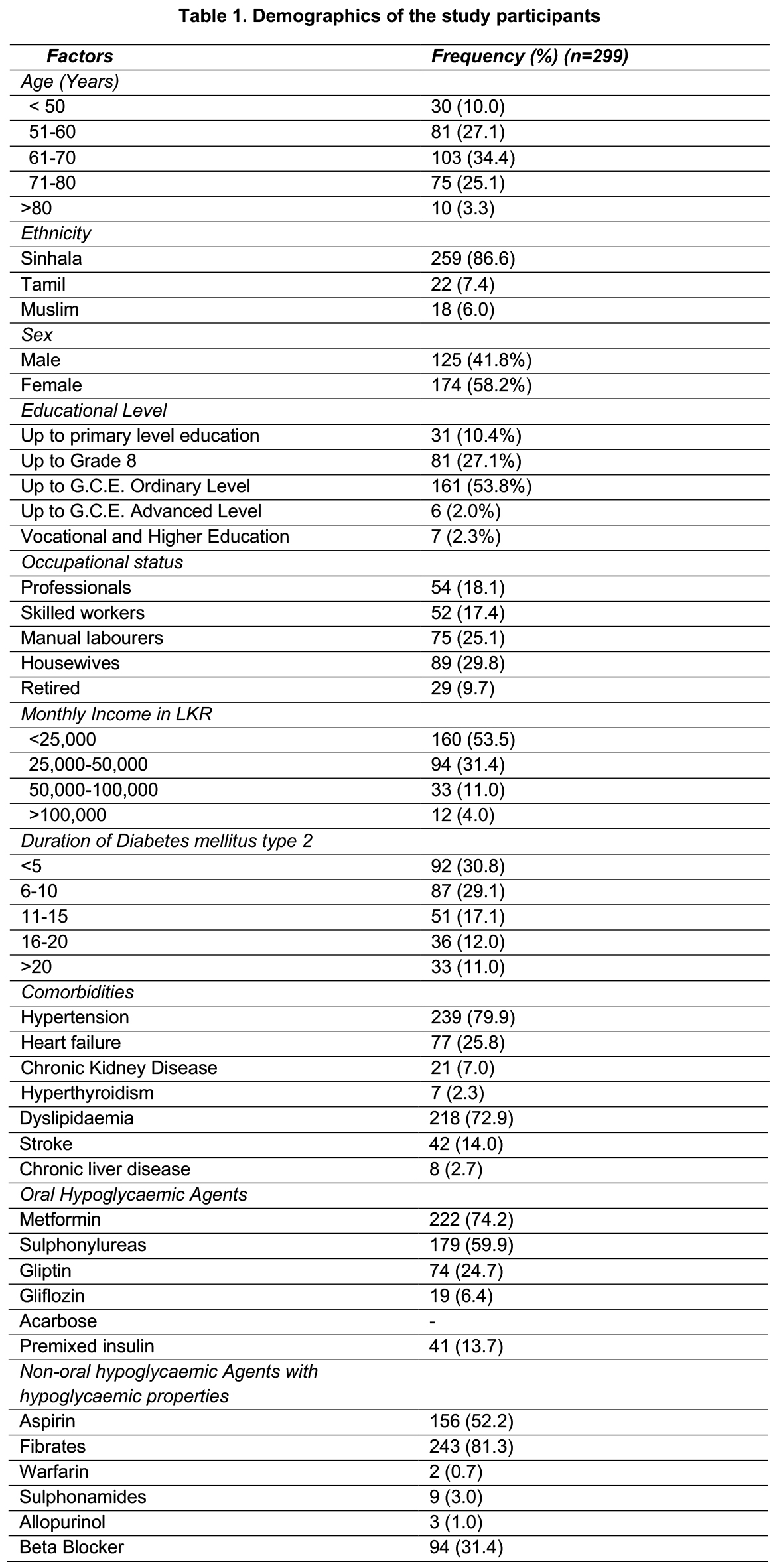

The demographic profile of the participants is depicted in Table 1. The majority of them were in the seventh decade of their lives and were females of Sinhala ethnicity. The largest group, comprising 92 participants (30.8%), had T2DM for less than 5 years followed by 29.1% having it for 6-10 years. The most prevalent comorbidity was hypertension (79.9%), and dyslipidaemia was the second (27.1%). Less common comorbidities include hyperthyroidism and chronic liver disease. (Table 1)

Metformin was the most widely used oral hypoglycaemic agent (74.2%) followed by sulphonylureas (59.9%). Gliptins were used by one-quarter of the participants while gliflozins were taken by 6.4%. Acarbose was not used by any participants. Premixed insulin was used by 13.7% of the sample. Among the non-oral hypoglycaemic agents that are associated with a risk of hypoglycaemia aspirin was the most commonly reported 52.2%. Other such agents included fibrates, warfarin, beta-blockers and sulphonamides. (Table 1)

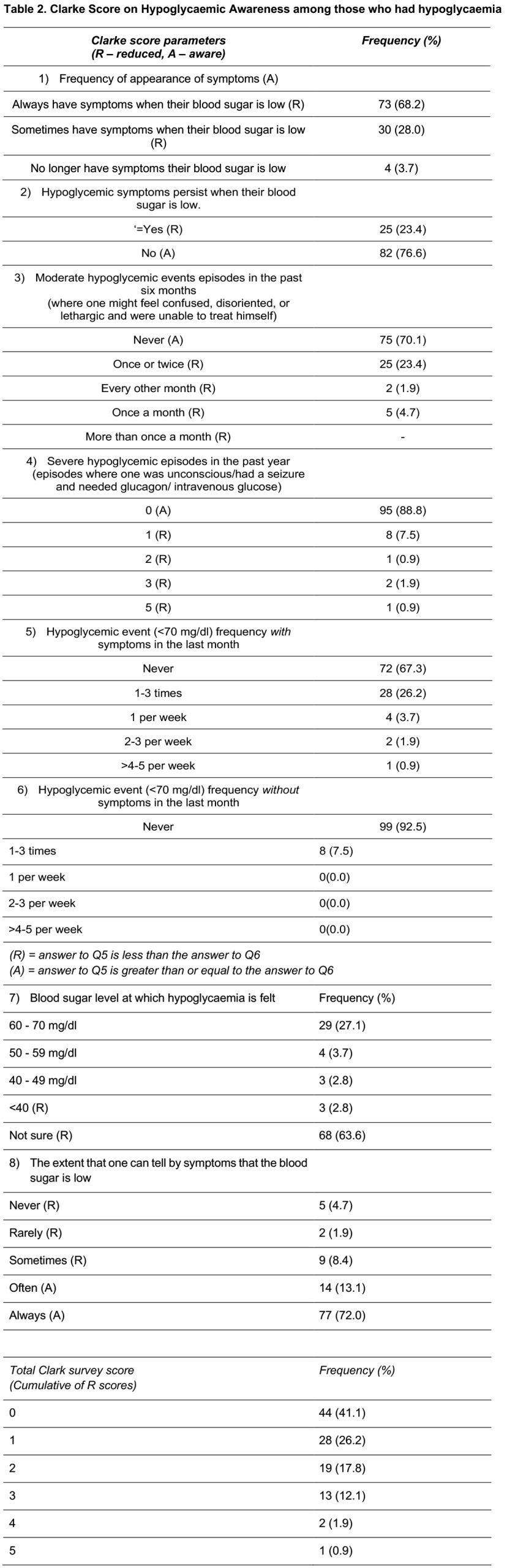

The most common Clarke score for hypoglycaemic awareness was 0, reported by 41.1% followed by scores 1 (26.2%) and 2 (17.8%) in the aware category. The indeterminant category (score 3) was less common (12.1%). Those in the unaware category (>4) were rare with only 2 participants (1.9%) scoring 4 and 1 participant (0.9%) scoring 5. Among those who had hypoglycaemia with regards to symptoms with low blood sugar, 5 participants (23.4%) indicated that they no longer experience these symptoms, while 82 participants (76.6%) continue to experience them. In this same group a majority of 75 participants (70.1%), reported never experiencing moderate hypoglycaemic events during the last 6 months. In contrast, 25 participants (23.4%) experienced such events once or twice, while 5 participants (4.7%) reported having them once a month. Only 2 participants (1.9%) experienced moderate hypoglycaemic events every other month in the last 6 months. A majority of 95 participants (88.8%), reported experiencing no severe hypoglycaemic episodes during this period. In a smaller group, 8 participants (7.5%), had one severe episode, while 2 participants (1.9%) experienced three episodes. Additionally, 1 participant (0.9%) reported having either two or five severe episodes. A majority of 72.0%, reported that they can always tell when their blood sugar is low. A smaller group of 13.1%, noticed low blood sugar often while 8.4% of participants sometimes recognized it. A proportion of 4.7% never experienced this awareness. This indicates that while many patients are attuned to their hypoglycaemic symptoms, a notable minority struggle with recognition, which may increase their risk of severe hypoglycaemia. (Table 2)

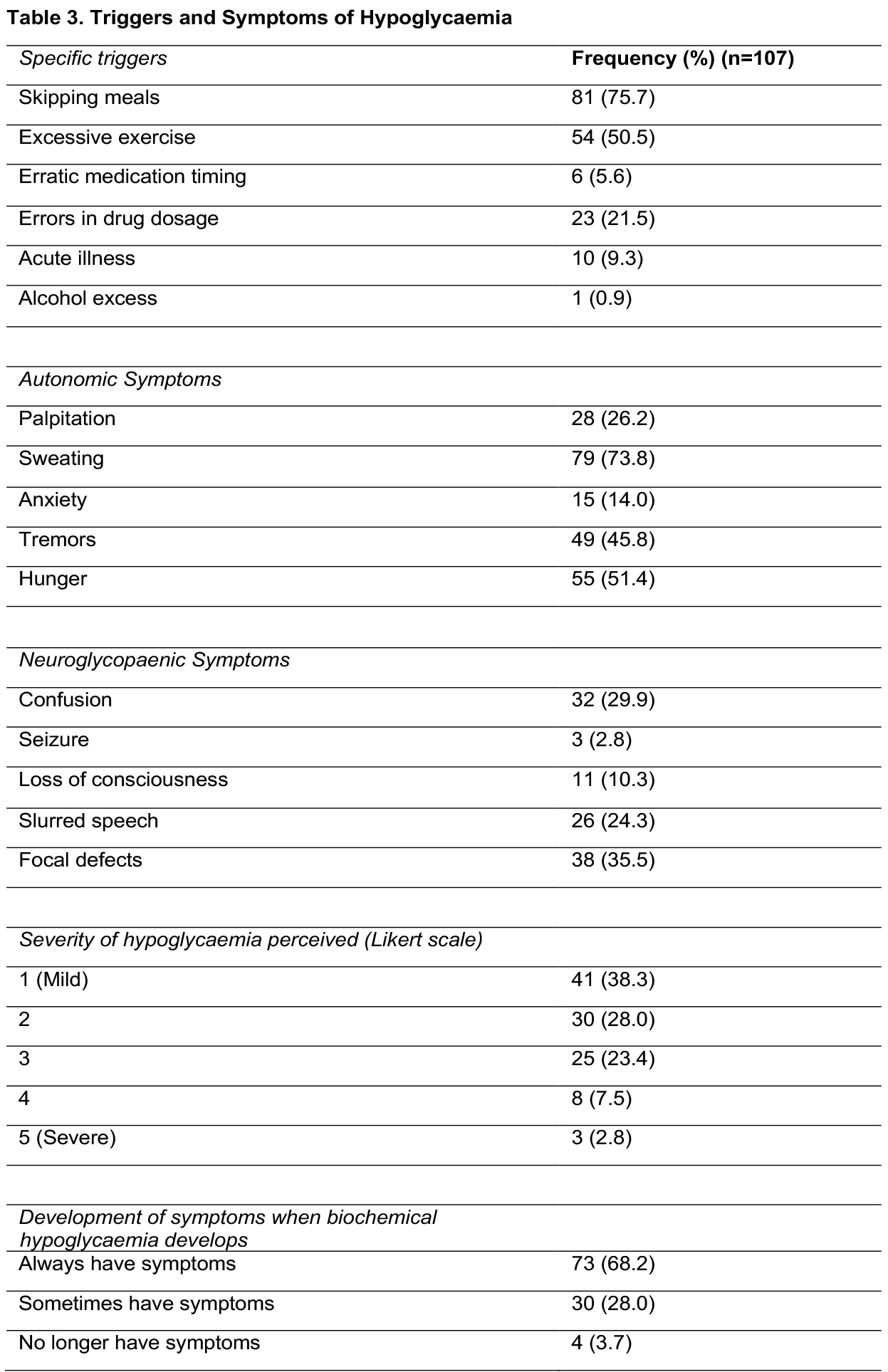

Meal skipping was the most significant trigger for hypoglycaemic episodes among them followed by excessive physical activity and dosage errors. Sweating was the most common autonomic symptom (73.8%). Other autonomic symptoms included hunger (51.4%), tremors (45.8%), palpitations (26.2%) and anxiety (14.0%). Focal deficits such as an arm or leg weakness were noted as a neuroglycopenic symptom in 35.5%. Other such symptoms were confusion (29.9%), slurred speech (24.3%), loss of consciousness (10.3%) and seizures being the least common (2.8%). With regards to the perception of the episodes using a Likert scale, mild levels were reported in the majority (38.3%) while severe ones were seen in 2.8%. A majority of 68.2% consistently experienced symptoms whenever their blood sugar levels dropped. In contrast, 28% reported experiencing symptoms only occasionally, indicating variability in their responses to hypoglycaemia. Notably, 3.7% indicated that they no longer experience symptoms associated with hypoglycaemia (Table 3).

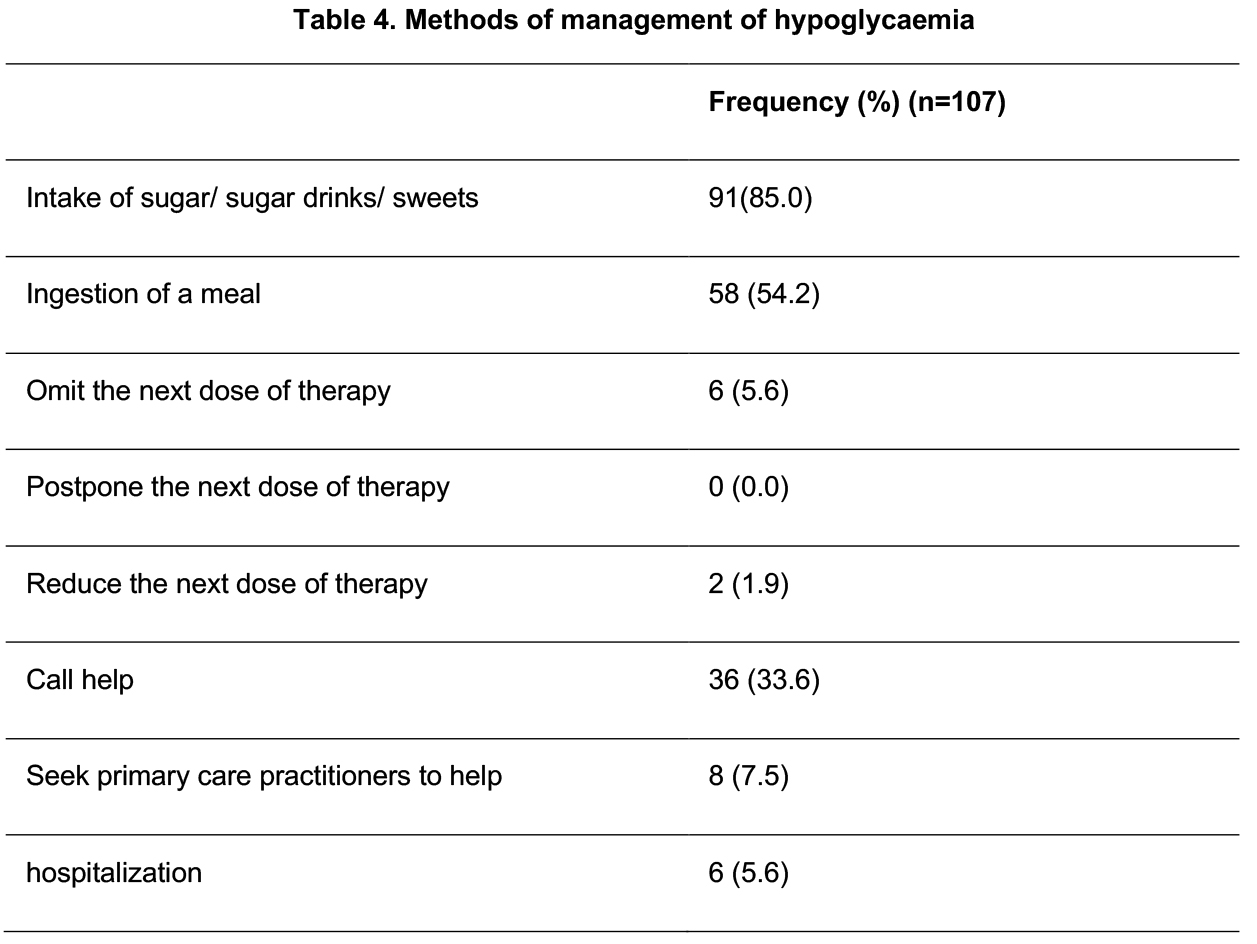

The most common approach to manage hypoglycaemia used was intake of sugar, sugary drinks, or sweets (85%). Additionally, 54.2% chose to ingest a meal to address low blood sugar. When seeking external help 36% would call for assistance, while a smaller number of 7.5% would seek help from their primary care provider. Hospitalization was a rare measure, with only 6 participants (5.6%) opting for this route. Methods such as omitting, postponing, or reducing the next dose of therapy are infrequently used. This data highlights the reliance on immediate dietary interventions for managing hypoglycaemic episodes among patients. (Table 4)

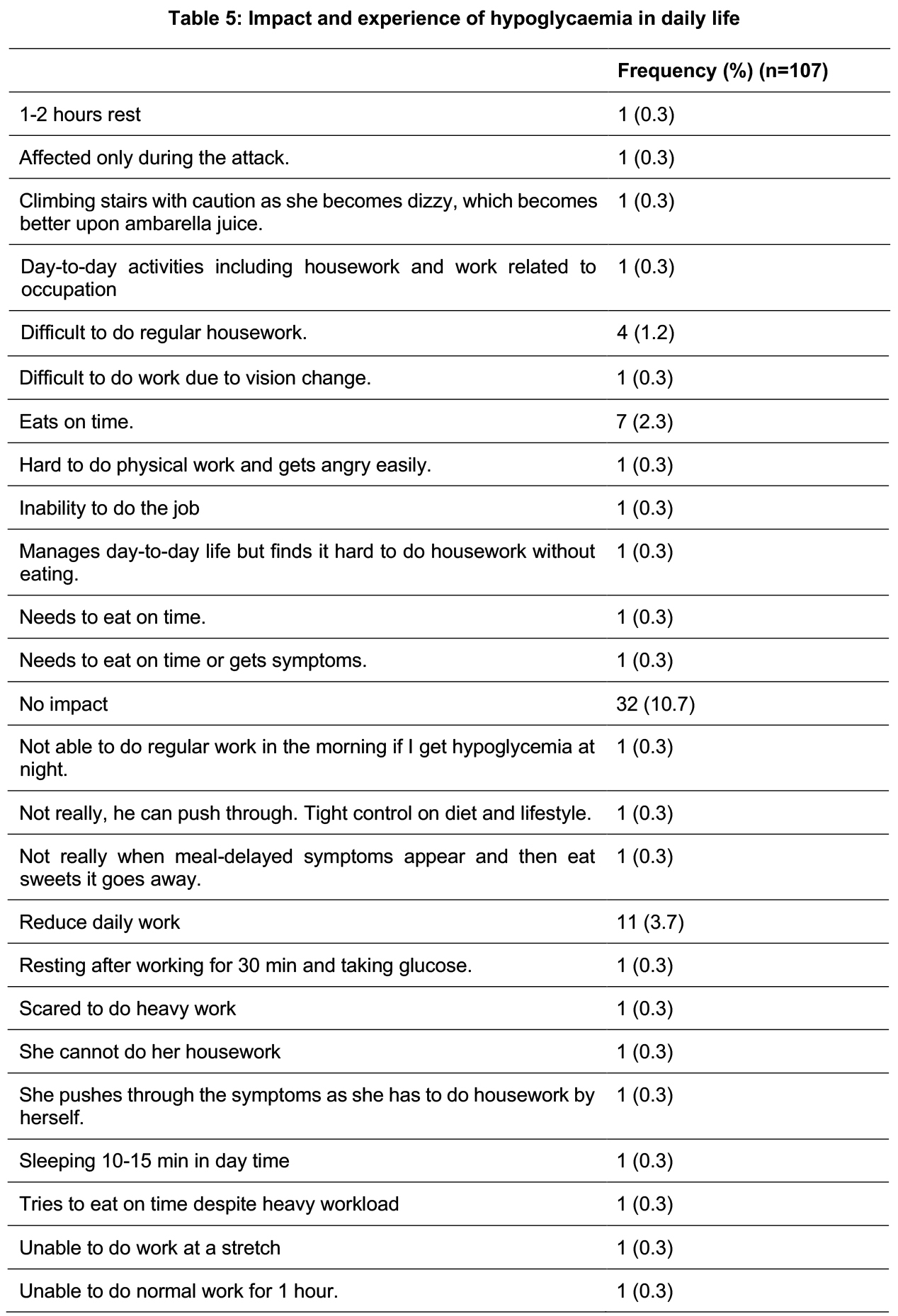

The impact and experience of hypoglycaemia on daily life are depicted in Table 5. It reflects that while many patients are attuned to their hypoglycemic symptoms, a notable minority struggle with recognition, which may increase their risk of severe hypoglycemia.

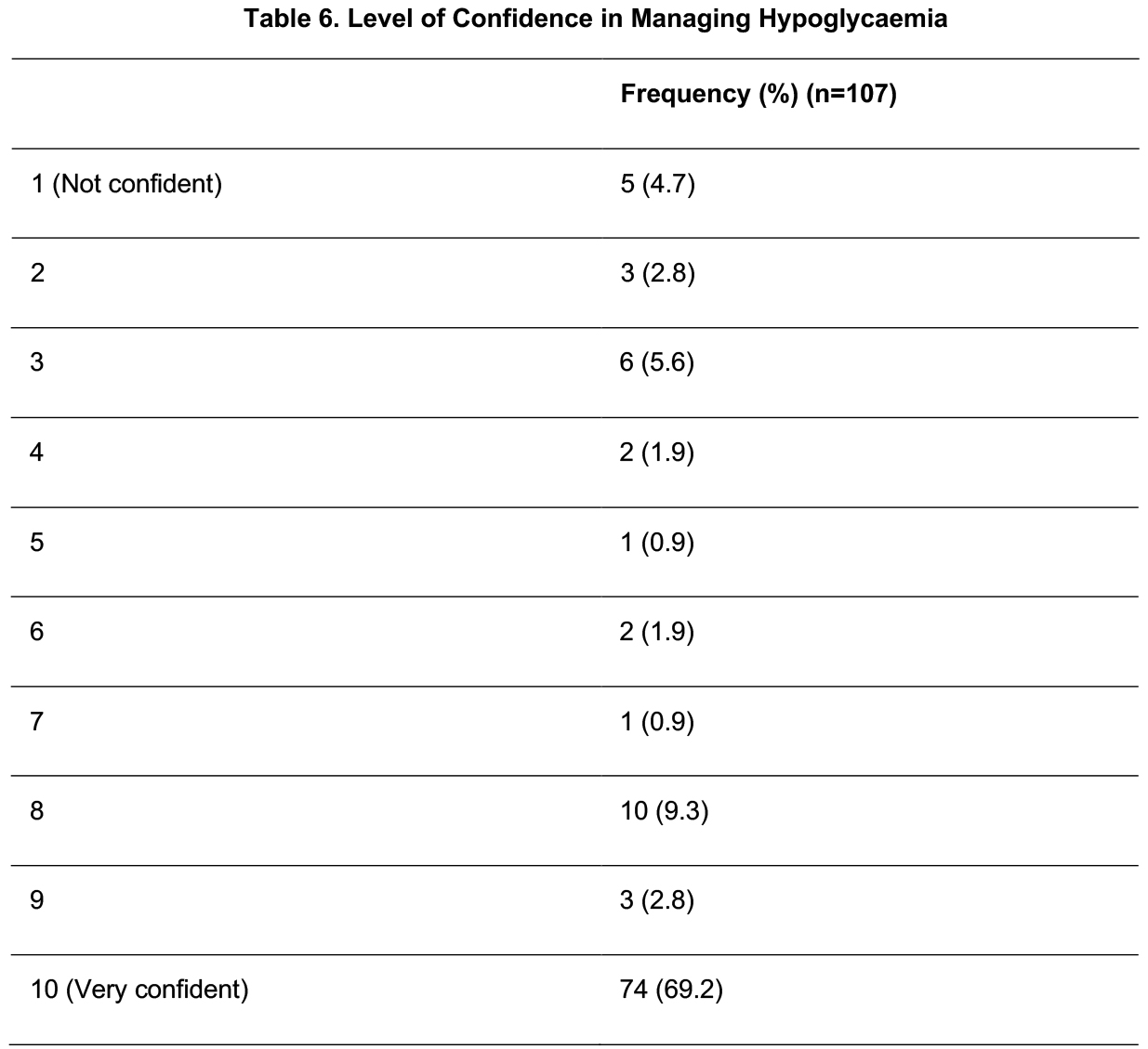

A predominant proportion expressed high confidence in their abilities or understanding of the subject. A proportion of 69.2% reported being “very confident,” indicating a strong sense of assurance. In contrast, only 4.7% of participants identified as “not confident”. (Table 6)

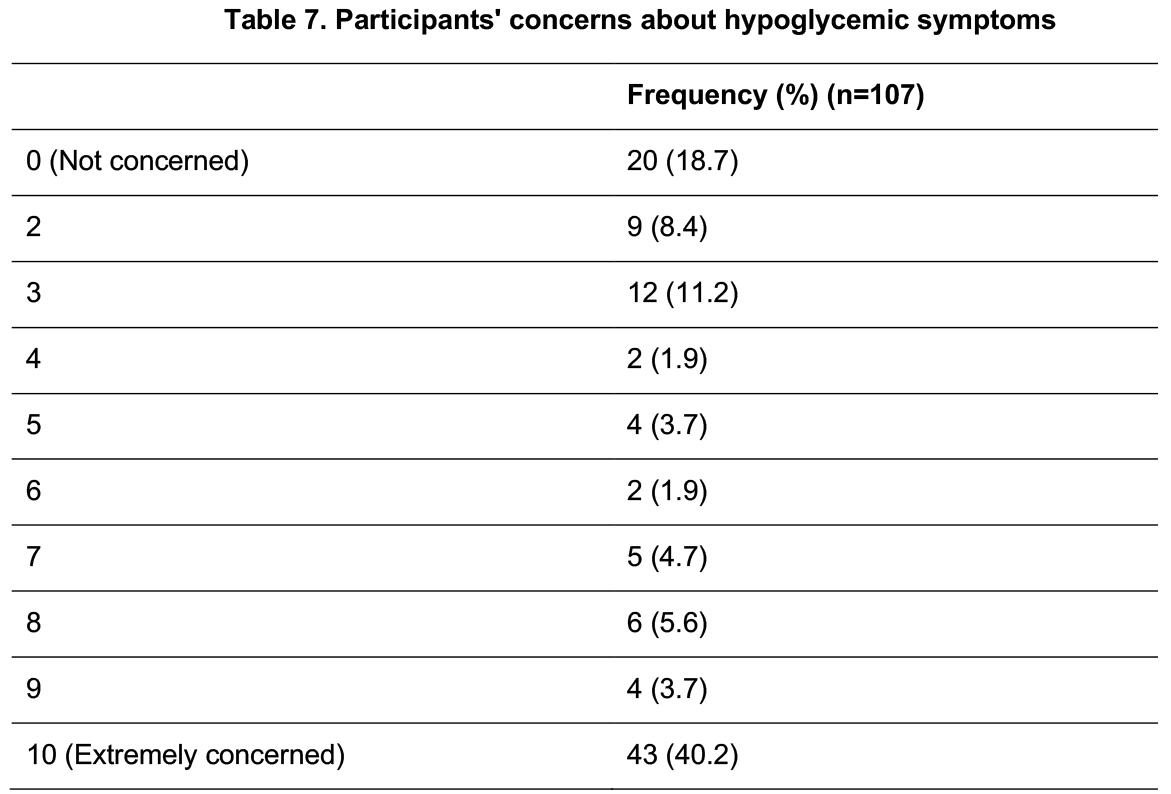

Participants’ concerns about hypoglycemic symptoms were assessed using a Likert scale where 0 being not concerned and 10 being extremely concerned. Less than 1/5th expressed none, while a significant portion, (40.2%), reported extreme concern. (Table 7)

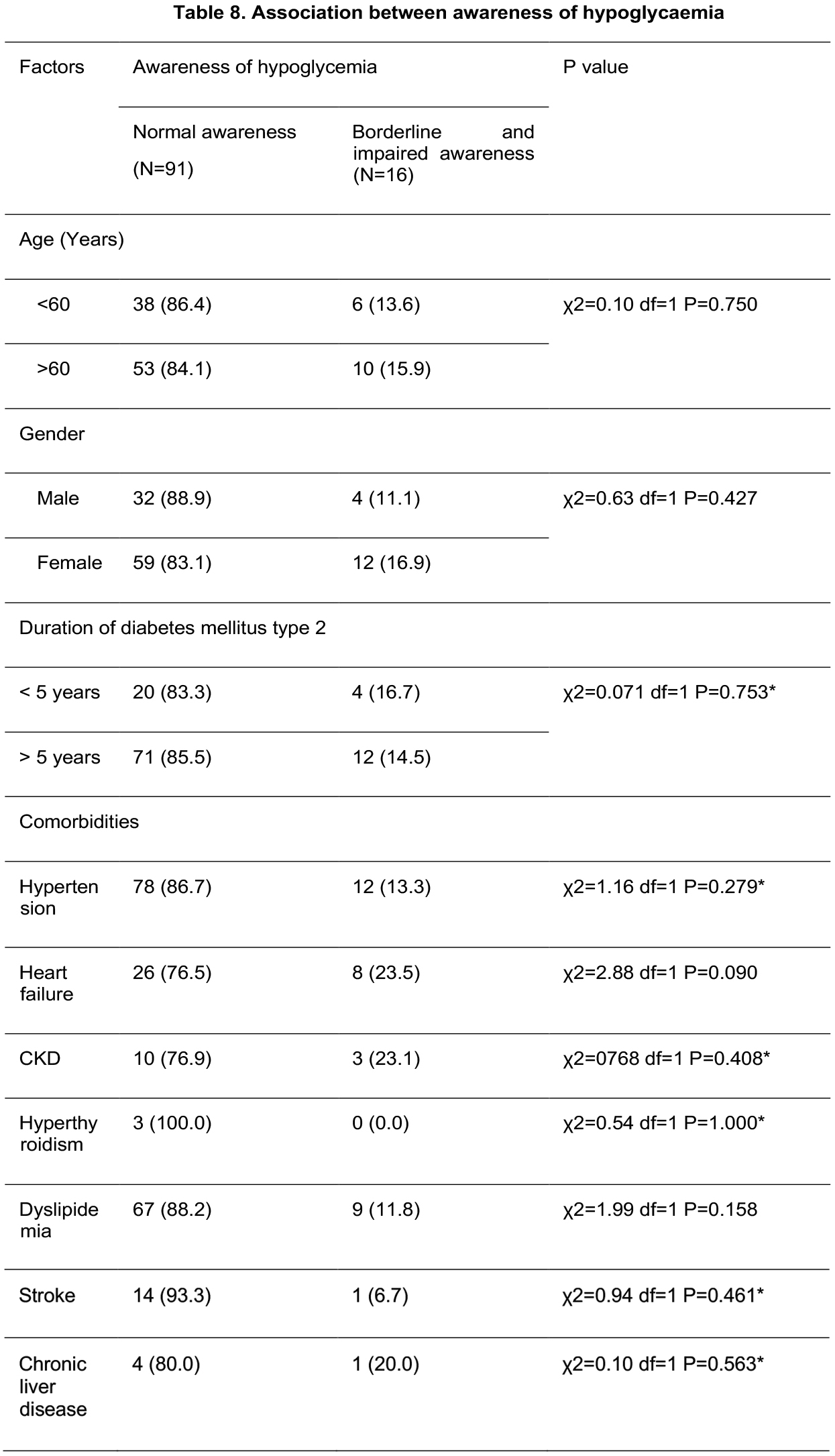

There was no significant difference in hypoglycaemia awareness between these age groups, gender, duration or associated comorbidities. (Table 8)

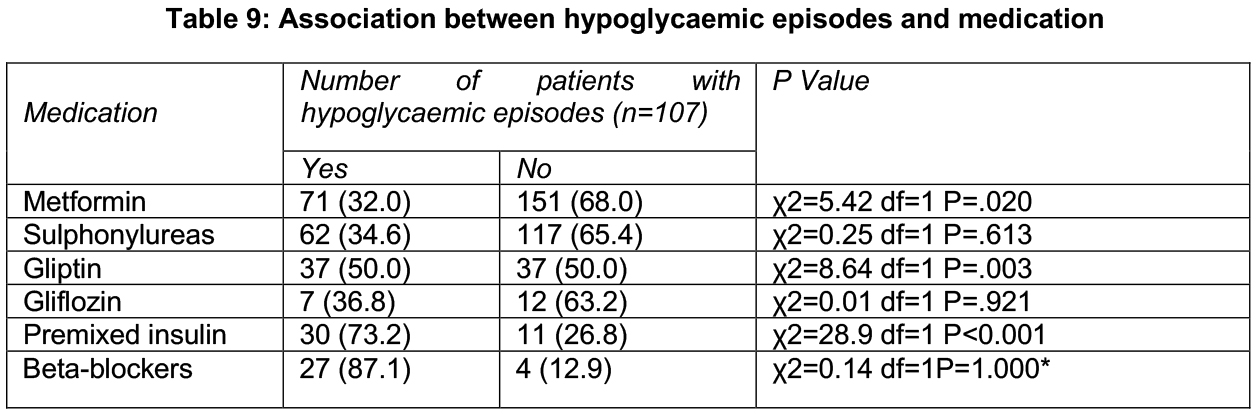

The data revealed significant associations between several medications and hypoglycemia. Metformin was associated with a higher incidence of hypoglycaemic episodes (p=0.020) while gliptins also showed a similar pattern (p=0.003). In contrast, sulphonylureas and gliflozins did not show significant associations with hypoglycaemia. Notably, premixed insulin was strongly linked to hypoglycaemic episodes (p<0.001). This suggests that patients using premixed insulin are at a significantly higher risk of experiencing hypoglycaemic episodes compared to those not using it. (Table 9)

Discussion

Disabling and life-threatening micro and macrovascular complications of T2DM highlight the need for optimum management.[2] The benefits of intensive glycaemic control in the prevention of these complications are well recognized.[11] However, it has been observed that most patients do not reach the optimum level of glycaemic control despite well-defined management protocols.[11] This, at least partly, is attributable to the fear of hypoglycaemia, both among patients and treating medical professionals.[12] In fact, in the ACCORD study, the higher mortality rate in the intervention arm is largely attributable to a higher incidence of hypoglycaemic events due to the rapid reduction of blood glucose.[13] Unpleasant symptoms of hypoglycaemia reduce patients’ compliance with and confidence in treatment and discourage medical professionals from adopting aggressive treatment strategies.[12] Insulin and oral antihyperglycemic agents, particularly those that increase insulin secretion independent of plasma glucose levels are the major causes for iatrogenic hypoglycaemia.

The female predominance in our study, despite the finding that male patients had a significantly higher incidence of hypoglycaemia, may suggest that gender-specific factors influence the risk of hypoglycaemia.[13] While males seem more prone to hypoglycaemia even with lower insulin doses, the overall higher number of female participants could indicate that the higher hypoglycaemic risk in males may be more pronounced in smaller male subgroups. This implies that while male patients require careful monitoring for hypoglycaemia, the study’s female-dominant sample may reflect the general population’s demographi distribution of healthcare access patterns. However, some studies suggest that women may experience more severe or symptomatic episodes, although this was not observed in our cohort. Further investigation is needed to explore potential subtle differences in hypoglycaemia experiences between genders.

Recent studies indicate that the prevalence of T2DM increases with age, which aligns with the findings of our study, where the majority of participants are aged 50 years and older.[14] This highlights the higher risk of T2DM in older populations.

Previous studies observed that occupation, knowledge, and education were characteristic factors of the occurrence of hypoglycaemia.[15] In our study, the majority of participants had a relatively low education level, with most completing up to O/L and many only reaching Grade 8. Many were housewives and manual labourers, reflecting lower-income occupations, with over half earning less than twenty-five thousand rupees monthly. This lower education and income likely contribute to their limited knowledge of hypoglycaemia, despite many having experienced it. These findings highlight the need for better education on hypoglycaemia management, particularly in lower-income and less-educated populations.

The study found that the prevalence of clinically significant hypoglycaemia among T2DM patients attending the clinics of Colombo South Teaching Hospital Kalubowila was 0.36%. Recent studies showed a hypoglycaemia prevalence of 21.7% among patients with T2DM, where incidents occurred with varying severity. This suggests that hypoglycaemia is a frequent complication in T2DM, especially among patients on insulin or sulfonylurea therapy.[16] In relation, our study found that a 0.3% prevalence of hypoglycaemia with normal awareness was observed in the majority of patients, while only 2.8% experienced impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia (IAH). In our study hypoglycaemia prevalence appears lower, but the presence of impaired awareness, even in a small fraction of patients, is significant. It highlights the risk of undetected hypoglycaemic episodes, which can lead to severe complications. Our findings suggest that, while hypoglycaemia remains a concern, the majority of patients maintain sufficient awareness, though targeted interventions are needed for those with impaired awareness to reduce the risk of severe events.

The results identified several key risk factors for hypoglycaemia, other than older age and other demographic factors, longer duration of diabetes, and the use of insulin was significant. These findings are consistent with the literature, where older adults with longer disease duration are at higher risk due to declining renal function and increased sensitivity to insulin.[17,18] The ACCORD study (2017) also highlighted these risk factors, emphasizing that patients with long-standing T2DM are particularly vulnerable to hypoglycaemic episodes. Our study thus supports the need for tailored therapeutic strategies for older patients with prolonged diabetes duration.

Regarding the role of medication in hypoglycaemia risk patients on insulin and gliptins had a significantly higher incidence of hypoglycaemia compared to those on metformin or other oral antidiabetic agents. This finding corroborates with previous studies, which also showed that insulin and sulfonylureas carry a higher risk of hypoglycaemia compared to other treatment modalities.[19] But in our study sulfonylurea is not significant. Sulfonylureas may not have been significant in our study due to a smaller sample size. Metformin rarely causes hypoglycaemia, which aligns with our study findings.[20] Beta-blockers did not show any association with hypoglycaemia in our study, which aligns with global research indicating a lack of significant connection between nondiabetic drugs like beta blockers and hypoglycaemia.[21] The results indicate that physicians must exercise caution when prescribing these medications, especially in patients prone to hypoglycaemic episodes, and that combination therapy should be individualized. Non-diabetic drugs are occasionally associated with hypoglycaemia, although the strength of their causal relationship is often debated. In our study, aspirin and fibrates were the most commonly used non-diabetic medications. Despite their frequent prescription, these drugs are not strongly linked to hypoglycaemia. The reporting of hypoglycaemia in association with these drugs may reflect their common use rather than a direct cause. Research on other medications such as heparin, which has been sporadically linked to hypoglycaemia in critically ill patients, highlights how alternative factors like illness and sepsis might play a more significant role than the medication itself.[22] This suggests that clinicians should consider multiple factors when assessing the potential for hypoglycaemia induced by non-diabetic drugs, especially when other underlying conditions or treatments (such as insulin or sulfonylureas) are present. The evidence supporting a direct link between these medications and hypoglycaemia remains weak and warrants further investigation.

The study also explored the relationship between hypoglycaemia and comorbid conditions, finding that patients with chronic kidney disease were more prone to hypoglycaemia. Other comorbidities such as hypertension, heart failure, hyperthyroidism, dyslipidaemia, stroke and chronic liver disease do not show significant association. This association has been well-documented, in recent studies with reporting that impaired renal function exacerbates the risk of hypoglycaemia, likely due to altered drug clearance and the heightened impact of blood sugar fluctuations.[23] These findings underscore the need for closer monitoring of at risk patients and potential adjustments in therapy.

Interestingly, lifestyle factors such as irregular meal patterns and excessive exercise were also associated with an increased risk of hypoglycaemia in this study. Poor dietary habits and alcohol use disrupt glucose metabolism, leading to unpredictable fluctuations in blood sugar levels. Our findings highlight the importance of lifestyle counselling in the management of diabetes, emphasizing regular meal intake and moderation in alcohol consumption to prevent hypoglycaemia.

The pattern of hypoglycaemia in our study reveals diverse frequencies and severities of episodes among participants. A significant portion experienced hypoglycaemic episodes, while the majority did not when the blood sugar level was below 70.2 mg/dl. Among those who reported hypoglycaemia, episodes varied from 1 to 4 per week for a small percentage, indicating a consistent occurrence of mild or moderate hypoglycaemia. However, most participants experienced hypoglycaemia less frequently, with the majority reporting more than weekly episodes and 18.5% experiencing them monthly. This range highlights that while some patients face regular glucose fluctuations, many encounter hypoglycaemia sporadically, which aligns with global data showing variability in frequency based on treatment regimens and patient adherence.

In terms of symptom recognition, the majority could always recognize when their blood sugar was low, which is crucial for preventing severe episodes. This high level of awareness helps to manage mild and moderate symptoms before they escalate. Autonomic symptoms, such as sweating and hunger, were commonly reported, while neuroglycopenic symptoms, such as confusion and slurred speech, were less frequent, typically appearing in more severe cases of hypoglycaemia.

The data from your study shows a clear distribution of hypoglycaemic episodes by severity, with mild episodes being the most commonly reported (38.3%), followed by moderate episodes (28.0%), and severe episodes being the least common (2.8%). These findings align with global trends, where mild hypoglycaemia tends to occur more frequently due to the increased sensitivity of blood glucose monitoring and the widespread use of insulin therapies.[24]

Moderate hypoglycaemia, which requires intervention but is not life-threatening, affected a notable percentage of your participants (23.4% reporting at least one episode in the past six months). This shows that moderate hypoglycaemia is a concern, particularly in patients undergoing intensive glucose control.

Severe hypoglycaemia, characterized by episodes requiring external assistance due to neuroglycopenic symptoms, is reported in a smaller proportion of patients. This lower incidence is consistent with international studies, where severe hypoglycaemia is less common but can result in significant morbidity and hospitalizations, especially among older patients and those on insulin.[24] The severity of hypoglycaemia tends to increase with a more aggressive treatment regimen, which emphasizes the importance of balancing glycaemic control with the risk of hypoglycaemic episodes.

In terms of symptom recognition, the majority (72.0%) could always recognize when their blood sugar was low, which is crucial for preventing severe episodes. This high level of awareness helps to manage mild and moderate symptoms before they escalate. Autonomic symptoms, such as sweating (73.8%) and hunger (51.4%), were commonly reported, while neuroglycopenic symptoms, such as confusion (29.9%) and slurred speech (24.3%), were less frequent, typically appearing in more severe cases of hypoglycaemia.

The study also explored the impact of hypoglycaemia on patients’ quality of life. The majority hadn’t been impacted. But found that recurrent hypoglycaemia significantly reduced both physical and emotional well-being. Patients reported anxiety, fear of future episodes, and restrictions in daily activities, similar findings in a recent study, which highlighted the psychological burden of hypoglycaemia.[25] Our results reinforce the importance of not only addressing the physical management of hypoglycaemia but also offering psychological support and counselling for affected individuals.

Regarding the awareness of hypoglycaemia, the majority had a good awareness. A subset of patients in our study exhibited hypoglycaemia unawareness, where they failed to recognize the early symptoms of low blood sugar. Repeated hypoglycaemic episodes blunt the body’s response to low glucose levels. This poses a significant risk for severe hypoglycaemia and calls for strategies such as adjusting treatment targets and using CGM to better manage these patients. Awareness is not associated with age, gender demographic factors and duration of the DM.

The management of hypoglycaemia among patients in this study primarily involves immediate intake of sugar, sugary drinks, or sweets, as reported by the majority of participants. This is consistent with standard recommendations for quick hypoglycaemia management, which emphasize rapid carbohydrate ingestion to restore blood glucose levels. Additionally, nearly half of the participants chose to manage their symptoms by ingesting a meal, which can help maintain stable blood sugar levels post-episode. External support was sought by 33.6% of participants, reflecting a reliance on assistance during more severe or prolonged episodes. Seeking medical help from a general practitioner or hospitalization was rare, suggesting that most patients manage mild or moderate hypoglycaemia independently. The infrequent use of methods such as adjusting the next dose of therapy highlights that proactive insulin or medication modification is not commonly adopted by these patients. This aligns with global findings that emphasize immediate symptom management over treatment adjustment in acute hypoglycaemic events.

The prevention of hypoglycaemia among participants in this study showed that only a small proportion made modifications to their daily routines to manage their condition. Strategies included adjusting insulin doses, adhering to timely meals, modifying meal plans, and reducing daily work intensity. These personal interventions align with global recommendations, which emphasize regular monitoring of blood glucose levels, proper timing of meals, and medication adjustments to prevent hypoglycaemic episodes.[26] However, the fact that 74.8% of participants did not implement preventive changes indicates a significant gap in proactive management.

This gap might be partially explained by the lack of education or guidance. While a significant majority of participants had received education on managing and preventing hypoglycaemia, a smaller percentage had not. Education plays a critical role in empowering patients to make necessary lifestyle adjustments and engage in effective self-care. Studies have consistently shown that patients who receive proper guidance on hypoglycaemia management are better equipped to prevent severe episodes. The data suggests that while most participants were educated, there remains room for improvement, particularly in translating education into practical, everyday strategies to prevent hypoglycaemia.

Limitations

There are a few limitations in our study. The sample size, while adequate for identifying trends, may not fully capture the entire population of T2DM patients in Sri Lanka. Additionally, our reliance on patient self reporting for some data points, such as hypoglycaemia symptoms and lifestyle factors, introduces the potential for recall bias. Additionally, the study only assessed a limited number of non-diabetic drugs, leaving other potentially hypoglycaemia-inducing medications unexplored. Lastly, the cross-sectional nature of the study limits the ability to establish causal relationships between variables.

Recommendations

The study on clinically significant hypoglycaemia among T2DM patients suggests several key recommendations. To improve management, there should be enhanced patient education focusing on hypoglycaemia awareness, glucose monitoring, and medication safety. Regular glucose monitoring and optimized clinic practices are advised to ensure consistent care. A multidisciplinary approach, integrating endocrinologists, dietitians, and diabetes educators, could offer a comprehensive management strategy. Longitudinal studies are recommended to assess long-term intervention effects. Developing patient support systems and proposing policy changes to healthcare facilities could further improve care and resource allocation. These recommendations aim to better manage and prevent hypoglycaemic events in T2DM patients.

Conclusion

This study aimed to determine the prevalence and patterns of hypoglycaemia among T2DM patients at Colombo South Teaching Hospital, Kalubowila. It found a low prevalence of hypoglycaemic episodes, with the majority having mild to moderate episodes. Key risk factors included insulin therapy, gender, age, educational level and occupation. Most patients managed their hypoglycaemia with sugar intake, while fewer made lifestyle changes or sought medical help. The findings highlight the importance of regular monitoring and personalized management to improve patient outcomes and reduce hypoglycaemic risks.

Ethics approval and consent to participate: Consent and Ethics approval from the research committee of the Colombo South Teaching Hospital. Our study did not include any interventions on participants.

Availability of data and material: The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests: No financial or nonfinancial competing interests

Funding: None

Authors’ contributions: GSH, SHS and SFHDS contributed to the literature search, acquisition of data, analysis of data, interpretation of data, and drafting of manuscript. The conceptualization of the study was done by SFHDS who was the overall supervisor

List of Abbreviations:

T1DM – Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus

T2DM – Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

References

- Jayawardena R, Ranasinghe P, Byrne NM, Soares MJ, Katulanda P, Hills AP. Prevalence and trends of the diabetes epidemic in South Asia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2012;12:380. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-380.

- Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2013. Diabetes Care 2013;36:S11–66. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc13-S011.

- Thrasher J. Pharmacologic Management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Available Therapies. Am J Med 2017;130:S4–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.04.004

- Amiel SA, Dixon T, Mann R, Jameson K. Hypoglycaemia in Type 2 diabetes. Diabetic Medicine 2008;25:245–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02341.x

- Donnelly LA, Morris AD, Frier BM, Ellis JD, Donnan PT, Durrant R, et al. Frequency and predictors of hypoglycaemia in Type 1 and insulin-treated Type 2 diabetes: a populationbased study. Diabetic Medicine 2005;22:749–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01501.x

- Miller CD, Phillips LS, Ziemer DC, Gallina DL, Cook CB, El-Kebbi IM. Hypoglycaemia in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:1653. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.161.13.1653

- Altowayan A, Alharbi S, Aldehami M, Albahli R, Alnafessah S, Alharbi AM. Awareness Level of Hypoglycaemia Among Diabetes Mellitus Type 2 Patients in Al Qassim Region. Cureus 2023. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.35285

- Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report 2020. Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020; Volume 2: 2020.

- Dissanayake HA, Keerthisena GSP, Gamage KKK, Liyanage JH, Ihalagama IRHS, Wijetunga WMUA, et al. Hypoglycaemia in diabetes: do we think enough of the cause? An observational study on prevalence and causes of hypoglycaemia among patients with type 2 diabetes in an out-patient setting in Sri Lanka. BMC Endocr Disord 2018;18:35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-018-0264-0

- Samya V, Shriraam V, Jasmine A, Akila G V., Anitha Rani M, Durai V, et al. Prevalence of Hypoglycaemia Among Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in a Rural Health Center in South India. J Prim Care Community Health 2019;10:215013271988063. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150132719880638

- Lopez JMS, Bailey RA, Rupnow MFT. Demographic Disparities Among Medicare Beneficiaries with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in 2011: Diabetes Prevalence, Comorbidities, and Hypoglycemia Events. https://home.liebertpub.com/pop [Internet]. 2015 Aug 10 [cited 2024 Sep 9];18(4):283–9. Available from: https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/pop.2014.0115

- Bakar A, Qomariah SN, Santoso CH, Gustomi MP, Syaful Y, Fatmawa L. Factors the incidence of hypoglycemia in diabetes mellitus patients: A pilot study in the emergency room. Enfermeria Clinica. 2020 Jun 1;30:46–9.

- Al-Azayzih A, Kanaan RJ, Altawalbeh SM, Alzoubi KH, Kharaba Z, Jarab A. Prevalence and predictors of hypoglycemia in older outpatients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. PLoS One [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Sep 9];19(8):e0309618. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0309618

- Viswanathan M, Joshi SR, Bhansali A. Hypoglycemia in type 2 diabetes: Standpoint of an experts’ committee (India hypoglycemia study group). Indian journal of endocrinology and metabolism. 2012 Nov 1;16(6):894-8.

- Ahren B. Avoiding hypoglycemia: a key to success for glucose-lowering therapy in type 2 diabetes. Vascular health and risk management. 2013 Apr 24:155-63.

- Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Byington RP. i wsp. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:2545-59.

- Li FF, Zhang Y, Zhang WL, Liu XM, Chen MY, Sun YX, Su XF, Wu JD, Ye L, Ma JH. Male patients with longstanding type 2 diabetes have a higher incidence of hypoglycemia compared with female patients. Diabetes Therapy. 2018 Oct;9:1969-77.

- Buse JB, ACCORD Study Group. Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial: design and methods. The American journal of cardiology. 2007 Jun 18;99(12):S21-33.

- Cryer PE, Davis SN, Shamoon H. Hypoglycemia in diabetes. Diabetes care. 2003 Jun 1;26(6):1902-12.

- Nasri H, Rafieian-Kopaei M. Metformin: current knowledge. Journal of research in medical sciences: the official journal of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. 2014 Jul;19(7):658.

- Murad MH, Coto-Yglesias F, Wang AT, Sheidaee N, Mullan RJ, Elamin MB, Erwin PJ, Montori VM. Drug-induced hypoglycemia: a systematic review. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2009 Mar 1;94(3):741-5.

- Seltzer HS. Drug-induced hypoglycemia: A review based on 473 cases. Diabetes. 1972 Sep 1;21(9):955-66.

- Moen MF, Zhan M, Walker LD, Einhorn LM, Seliger SL, Fink JC. Frequency of hypoglycemia and its significance in chronic kidney disease. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2009 Jun 1;4(6):1121-7.

- Besen DB, Surucu HA, Koşar C. Self-reported frequency, severity of, and awareness of hypoglycemia in type 2 diabetes patients in Turkey. PeerJ. 2016 Dec 13;4:e2700.

- Lopez JM, Annunziata K, Bailey RA, Rupnow MF, Morisky DE. Impact of hypoglycemia on patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and their quality of life, work productivity, and medication adherence. Patient preference and adherence. 2014 May 8:683-92.

- Nakhleh A, Shehadeh N. Hypoglycemia in diabetes: An update on pathophysiology, treatment, and prevention. World journal of diabetes. 2021 Dec 12;12(12):2036.