Medical Journal

Published by

Faculty of Medical Sciences,

University of Sri Jayewardenepura,

Nugegoda,

Sri Lanka.

Leading Article

Compassion and Empathy in Healthcare: Bridging Science and Humanity

Dr. Shehan Silva

Senior Lecturer in Medicine, Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Sri Jayewardenepura

dshehans@sjp.ac.lk

Comfort Always?

Healthcare, a profession of paradoxes demands rigorous scientific precision as well as a profound understanding of human emotion and vulnerability. The synthesis of these elements defines the art of medicine. Empathy and compassion, far from being mere add-ons to clinical expertise, serve as foundational principles that can significantly influence patient outcomes. These qualities allow healthcare professionals to see beyond the symptoms, diagnoses, and treatment regimens to engage with patients as individuals with unique stories, fears, and hopes. As technology advances, the focus on efficiency often threatens to depersonalize healthcare. From robotic assisted surgeries to artificial intelligence in diagnostics, modern medicine increasingly emphasizes technological precision.

However, this shift poses the risk of diminishing the human connection essential to healing. A patient may marvel at the accuracy of a machine-generated diagnosis but still crave the warmth of a reassuring conversation with a caregiver. The adage ‘comfort always highlights the timeless need for human touch amidst technological progress. The challenge lies in integrating empathy and compassion into modern clinical settings without compromising efficiency or accuracy. Patients who perceive their healthcare providers as empathetic are more likely to adhere to treatment plans, leading to better health outcomes. Furthermore empathetic communication reduced hospital readmissions. This is a compelling argument for embedding emotional intelligence in medical education and practice.

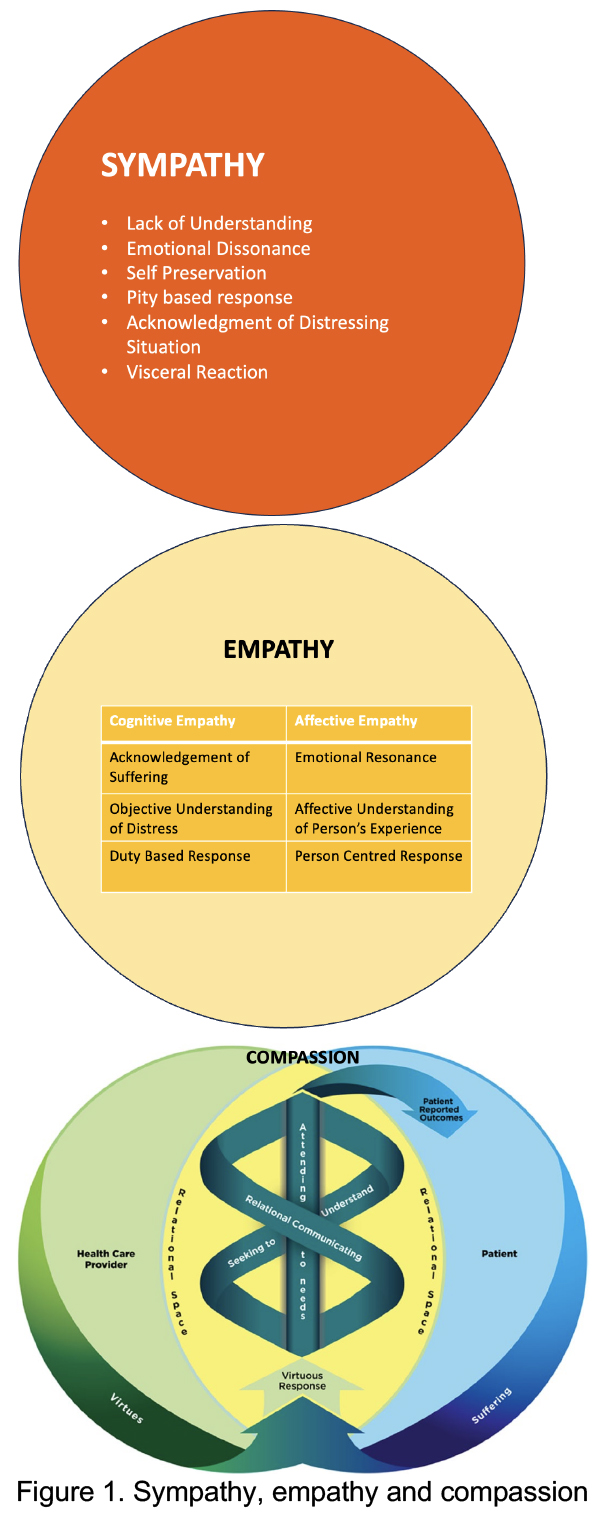

Understanding Sympathy, Empathy, and Compassion

The nuances between sympathy, empathy, and compassion are critical to understanding their application in healthcare. Sympathy, while heartfelt, often creates a one-sided dynamic. Pity, which frequently accompanies sympathy, may unintentionally undermine a patient’s sense of dignity. For instance, saying, “I’m sorry this is happening to you,” acknowledges pain but lacks the depth to foster meaningful connection or action.

Empathy, by contrast, requires a deeper emotional engagement. It involves imagining oneself in another’s situation, experiencing their feelings, and responding with understanding. Empathy, however, is not without challenges. Continuous exposure to patients’ suffering can lead to what psychologists term “empathic distress.” This phenomenon, if unchecked, may result in burnout, decreased job satisfaction, and even withdrawal from patient interactions.

Compassion takes empathy a step further. It combines emotional resonance with a commitment to action. Compassionate care not only recognizes and feels another’s pain but actively seeks to alleviate it. This distinction is pivotal in healthcare. For example, a compassionate nurse doesn’t stop at acknowledging a patient’s anxiety; they work to address it by explaining procedures in layman’s terms or offering emotional support.

Moral Distress and Compassion Fatigue

Empathic distress, if not managed, can be debilitating. Healthcare professionals often report feelings of helplessness and frustration when they are unable to alleviate suffering. Implementing coping strategies, such as mindfulness or debriefing sessions, can mitigate these effects. Healthcare is fraught with ethical dilemmas where compassion intersects with professional obligations. For instance, consider the allocation of limited resources such as ICU beds or organ transplants. While compassion may drive a provider to advocate for a particular patient, ethical principles like justice require equitable distribution. Balancing these competing priorities demands nuanced judgment and a robust ethical framework.

Moral distress arises when external constraints prevent healthcare providers from acting in line with their ethical beliefs. A poignant example is end-of-life care in settings with conflicting legal, cultural, and personal perspectives. In countries like Sri Lanka, where euthanasia is not legally sanctioned, healthcare providers may feel torn between their professional responsibilities and the compassionate desire to honour a patient’s wishes.

Such situations can lead to profound emotional turmoil. Providers may feel they are failing in their duty to alleviate suffering, a core tenet of compassionate care. Over time, unresolved moral distress can contribute to burnout, withdrawal from patient care, or even career abandonment. To mitigate moral distress, healthcare institutions must foster environments that allow providers to voice their concerns and seek guidance. Regular ethics rounds, debriefing sessions, and peer support groups are invaluable in providing spaces for reflection and emotional processing. Additionally, institutions can offer resources such as access to ethics consultants or counsellors trained to navigate complex moral dilemmas.

Compassion fatigue, often misunderstood as a byproduct of caring too much (the cost of caring), is more accurately attributed to systemic failings such as understaffing and excessive workloads. Addressing these issues requires institutional changes, such as adequate staffing, fair compensation, and mental health support for caregivers. Compassion does not cause fatigue. However fatigue causes the inability to be compassionate. This underscores the need for systemic interventions to address root causes. The healthcare system itself often acts as a barrier to compassionate care, with time constraints, burnout, and a culture that does not prioritize compassion being a significant obstacle. As an example when a doctor is responsible for caring for too many patients in a shift, his ability to engage compassionately diminishes, not because they lack empathy but because the structural demands of their job make it impossible. Addressing compassion fatigue, therefore, requires systemic interventions. Adequate staffing, manageable workloads, fair compensation, and access to mental health resources are essential components of fostering an environment where compassion can thrive.

While systemic change is critical, healthcare professionals can also adopt individual strategies to build resilience. Mindfulness practices, regular self-care routines, and professional boundaries are essential tools. For instance, a doctor who feels emotionally drained after a particularly challenging shift might benefit from mindfulness exercises to recentre and recharge. Similarly, engaging in reflective writing or seeking peer support can help caregivers process their emotions and maintain their ability to connect compassionately with patients.

A Case Study

A 65-year-old patient with terminal cancer is admitted to the ICU with severe respiratory distress. Despite the clear progression of the disease, the patient’s family insists on aggressive treatment, hoping for a miracle. The attending physician, however, believes that palliative care would better serve the patient by prioritizing comfort and dignity over invasive procedures that are unlikely to improve outcomes. This situation highlights a profound ethical conflict. On one hand, compassion for the family might lead the physician to honour their wishes, respecting their emotional need to exhaust every possible option. On the other hand, the principle of beneficence demands that the physician recommend the course of action that aligns with the patient’s best interests and minimizes harm. Nonmaleficence, or “do no harm,” further supports the physician’s reluctance to pursue aggressive interventions that could prolong suffering.

Resolving such dilemmas requires clear communication, empathy, and ethical reasoning:

- Engaging with the Family: The physician might begin by acknowledging the family’s fears and hopes, demonstrating empathy for their emotional state. Active listening and open-ended questions can help the family feel heard and respected.

- Providing Clarity: Using plain language, the physician can explain the patient’s prognosis, the likely outcomes of aggressive treatment, and the benefits of palliative care. Providing this information transparently helps the family make informed decisions.

- Invoking Ethical Principles: The physician can articulate the ethical reasoning behind their recommendations, emphasizing the importance of the patient’s comfort and dignity.

- Collaborative Decision-Making: Involving the family in the decision-making process fosters trust and reduces the likelihood of conflict. If necessary, the physician might enlist the help of an ethics committee or palliative care specialist to mediate the discussion.

The Spiritual and Aesthetic Foundations of Compassion

All across cultures emphasize compassion as a care. Buddhism’s Metta teaches universal lovingkindness, while Christianity’s Agape embodies unconditional love. These teachings offer profound insights into the caregiver-patient relationship. Art and literature have long celebrated the power of compassion in healing. The Good Samaritan parable illustrates the importance of transcending cultural and social barriers to alleviate suffering. Similarly, the Buddha’s account of ministering to the Puttigatissa emphasize the holistic nature of care. These narratives remind healthcare providers that their role extends beyond physical healing to addressing emotional and spiritual needs. Spiritual practices like mindfulness and gratitude journaling are increasingly being integrated into healthcare training programs. These practices enhance caregivers’ ability to stay present, reduce stress, and maintain a compassionate outlook.

Integrating Compassion into Clinical Practice

Empathy training programs have gained traction in medical education. Role-playing exercises, reflective writing, and narrative medicine are effective tools for cultivating emotional intelligence. For instance, medical students who participate in reflective writing workshops often report greater understanding of their patients’ perspectives and improved communication skills. Programs focusing on communication and relational skills can enhance the therapeutic alliance and make compassion skills more tangible for healthcare providers.

Creating a culture of compassion requires systemic change. Hospitals must implement policies that prioritize patient-centred care while supporting staff well-being. As an example, introducing flexible schedules, providing mental health resources, and fostering a supportive work environment can mitigate burnout and compassion fatigue. Effective compassion interventions should span organizational levels, focusing on building connections and cultural safety. Leadership involvement is crucial for transforming healthcare culture and promoting compassion as a core value. Encouraging selfcare and providing role models can facilitate the cultivation of compassion among medical students and professionals.

Challenges in Fostering Compassion

Cultural attitudes toward emotional expression can influence the delivery of compassionate care. In some societies, stoicism is valued, making it challenging for caregivers to gauge and respond to patients’ emotional needs. Training programs that address cultural competence can help healthcare providers navigate these complexities. Systemic barriers, such as time constraints and bureaucratic pressures, also hinder compassionate care. Overcoming these obstacles requires rethinking healthcare delivery models to prioritize meaningful patient interactions.

Implicit biases can undermine compassionate care, leading to disparities in treatment. Ongoing training in cultural humility and bias recognition is essential for ensuring equitable care. Studies show that healthcare providers who engage in regular self-reflection are better equipped to recognize and address their biases.

Expanding Ethical Support in Healthcare

Ultimately, addressing the ethical challenges of compassionate care requires both systemic and individual interventions. Healthcare institutions must prioritize ethics training, provide forums for discussion, and ensure that policies support both patients and caregivers. Simultaneously, caregivers must cultivate emotional resilience and seek support when navigating morally complex situations. The integration of empathy, ethical reasoning, and professional judgment ensures that healthcare remains not only scientifically advanced but also profoundly humane. By addressing moral distress and fostering environments where compassion can flourish, the healthcare community can uphold its commitment to alleviate suffering and restore dignity, even in the face of the most challenging ethical dilemmas.

Compassion fosters not only professional excellence but also personal growth. By engaging deeply with patients, healthcare providers often develop a broader perspective on life, enhancing their emotional resilience. This growth benefits not only their patients but also their relationships outside of work. Studies have also shown that compassionate care leads to improved patient outcomes. Patients who perceive their caregivers as compassionate experience lower levels of pain and anxiety, adhere more faithfully to treatment plans, and report higher satisfaction with their care.

Conclusion: A Call to Action

Compassion and empathy are indispensable in healthcare. They are not mere ideals but practical tools that enhance patient care and caregiver well-being. However, fostering these qualities requires a collective effort—from individual caregivers to institutional leaders. This philosophy should guide every aspect of medical practice, ensuring that the human element remains central in an increasingly technological world. By prioritizing empathy and compassion, the healthcare community can create a system that not only cures diseases but also heals individuals, restores dignity, and uplifts the human spirit.

References

- Jeanmonod, D., Irick, J., Munday, A. R., Awosika, A. O., & Jeanmonod, R. (2024). Compassion Fatigue in Emergency Medicine: Current Perspectives. Open access emergency medicine : OAEM, 16, 167–181. https://doi.org/10.2147/OAEM.S418935

- Lane, C.B., Brauer, E., & Mascaro, J. S. (2023). Discovering compassion in medical training: a qualitative study with curriculum leaders, educators, and learners. Frontiers in psychology, 14, 1184032. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1184032

- McCoy, M. (2024). Compassionate Practice: A Review and Framework for Integrating Medical Humanities into Pre-Medical and Medical Curricula. https://doi.org/10.15760/honors.1510

- Patel, S., Pelletier-Bui, A., Smith, S., Roberts, M. B., Kilgannon, H. J., Trzeciak, S., & Roberts, B. W. (2018). Curricula and methods for physician compassion training: protocol for a systematic review. BMJ Open, 8(9), e024320. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024320

- Pavlova, A., Paine, S. J., Tuato’o, A., & Consedine, N. S. (2024). Healthcare compassion interventions co-design and feasibility inquiry with clinicians and healthcare leaders in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Social science & medicine (1982), 360, 117327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2024.117327

- Sills-Maerov, M., & Valanci, S. (2024). The art and skills of compassion in practice. The International Journal of Whole Person Care, 11(1S), S11–S12. https://doi.org/10.26443/ijwpc.v11i1.395

- Sinclair, S., Beamer, K., Hack, T. F., McClement, S., Raffin Bouchal, S., Chochinov, H. M., & Hagen, N. A. (2017). Sympathy, empathy, and compassion: A grounded theory study of palliative care patients’ understandings, experiences, and preferences. Palliative medicine, 31(5), 437 447. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216316663499